WE GOT SHOT UP, SHOT AT AND SHOT DOWN

on 70th anniversary of German surrender

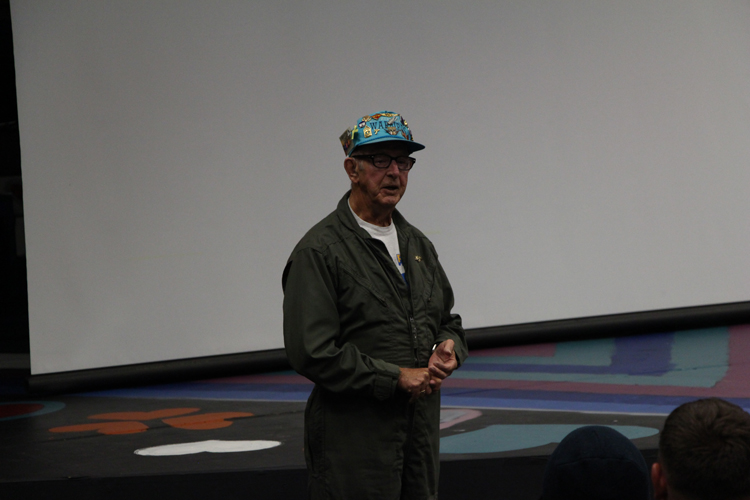

To honor the 70th anniversary of Germany’s surrender in World War II, over 50 students and community members gathered on May 8 in the Whipple Fine Arts Center to remember the world’s last great war. WWII veteran Leo Kraft spoke to the crowd about his time in the Marine Corp as a gunner aboard a dive bomber off the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific. Kraft, 91, recalled a timeline that led from his time in boot camp as a grunt, to some of the most dangerous battles of the Pacific theater.

ASUCC student senator Joshua Freidlin with the help of UCC professor Charles Young, organized the afternoon’s festivities. Before introducing Kraft, Young provided a sobering reminder to the crowd about how perilously close the world came to having a different outcome in the war.

“A lot of Americans today do not realize what a close call WWII was and how it could have turned out very, very different,” Young said. “Hitler played his cards wrong, fortunately for the world, in not taking out Britain first before taking on the Soviets and then the United States.”

The United Kingdom offered an enormous strategic advantage for Allied forces in their struggle with Nazi occupied Europe. Britain was the staging point for Operation Overload, commonly known as D-Day.

“Britain was an aircraft carrier right off the coast of Nazi held France,” Young said. “Had Britain fallen, we would have had to figure out how to get across 3,000 miles to invade fortress Europe. With all the resources of Eurasia that the Japanese, Italians and Germans would have commanded, it would have been a war going on for decades. We all know about German science, they came up with jet fighters before us. They came up with rockets, V-1 and V-2 before us. Given a few more years, they would have had the bomb, too, and they would have had a few more years. This is what I’m talking about, it was a close call.”

Young then introduced Kraft, reading a litany of medals the WWII veteran earned during the three tours he served in the South Pacific. Recipient of three Distinguished Flying Crosses, nine Navy Commendation Medals and a Presidential Unit Citation, Kraft earned three Purple Hearts during his 20 months of services in combat.

Raised on a farm in South Dakota, Kraft enlisted in the Marine Corp five months after Pearl Harbor.

“After boot camp, I went up to Camp Pendleton for more ground-pounding, which was infantry training,” Kraft said. “After going through the infiltration courses, marching 10 miles with a full pack and all of that other crap, I said to myself, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ Fortunately, there were some officers who came looking for volunteers to get into aviation.”

After nine months of total training, Kraft was sent to the Solomon Islands shortly after the battle of Guadalcanal. As a gunner aboard a Dauntless SBD (Scout Bomber Dive), Kraft and his pilot performed a wide-range of missions during their time patrolling the Solomon Islands.

“Our main job was to get subs, ships and to knock out the big guns,” Kraft said. “Knocking out the big guns was probably number one because then the big planes could come in and rack ’em off without getting blown apart. It was quite a challenge. We had twin 30s in the back, and you had 600 rounds for each one. Everyone tried to conserve as much ammunition as possible because we didn’t have too much to go around. We were always warned every time we left to make damn sure we hit what we were shooting at and not going out there and just busting away.”

Kraft talked candidly at length about the many dangers he faced during his combat tours, starting with a return from his very first mission.

“Down in Guadalcanal, I’m telling you that was a rough spot,” Kraft said. “On our first run from the New Hebrides, to Guadalcanal we had a real welcome. The Japanese happened to hit one of our ammo dumps. It looked like the Fourth of July. We were burning off our fuel for a half hour waiting to land.”

Kraft described the many intangibles that pilots had to deal with when flying in a WWII class dive bomber.

“At 16-18,000 feet it’s colder than hell,” Kraft said. “There are no heaters in those things. The only time we closed our canopy was when we went through a thunderstorm or rain. Other than that, it was open. If you get hit and it screws up your canopy, you won’t be able to get it open and you can’t get out, you’re stuck in there.”

Having their canopy open may have saved Kraft and his pilot’s lives following the aftermath of one of their missions. The experience resulted in both men receiving a Purple Heart.

“We got shot up, shot at and shot down,” Kraft said. “We had to ditch. But when we did, there was no ship around. There was nothing but water. After you hit the water, you have 30 seconds to get out of there. Get the pilot out, get your raft, push away and get as far away from the plane as possible so you don’t get sucked down with it when that thing goes down underneath water.”

The two men, both suffering from severe injuries, sat alone floating in the South Pacific waiting and hoping for rescue.

“We bounced around in that two-man raft for about six and a half hours when a Dumble, a PBY (search/rescue plane), came by and picked us up. Boy, I tell you when that guy opened up and let us in, I could have kissed that sucker.”

The dangers of operating a dive bomber were described in vivid detail by Kraft. The crowd sat in eerie silence as he recalled what it was like to lock onto a target and begin a dive from 18,000 feet.

“When we went down, a lot of times our wing-man bombed on us,” Kraft said. “We went down first, so we drew the fire. I’m telling you, going down on a ship, it was just like taking a fire poker and poking it into a fireplace, because everything was red coming up right at you. That was the problem of hitting a ship.”

A similar situation led to the closest call Kraft and his pilot faced. The WWII veteran talked about the near-death experience and how he nearly didn’t make it home alive.

“The closest call I think was this one time we were told to go out into this area where there was this ship,” Kraft said. “I don’t know what class it was, but it had a hell of a lot of guns. We had two wing-men and our job was to go out and pick that baby off. When we went out there, we found it. We were up about 18,000 feet when we started our dive. All the weapons that they had aboard that ship was shooting at us. It looked like we were diving into a ring of fire. All three of us dropped our bombs, when we got out of there we were all tore up. We had a hole between the pilot and I that was about two feet in diameter. You could have crawled through that. It somehow managed to not ruin any of the plane’s controls.”

.jpg)

Kraft did manage to spend some time on R & R, something all soldiers looked forward to for obvious reasons.

“They gave us a trip down to Sydney, Australia,” Kraft said. “I’m telling you, you had money on the books and you blew it, because you didn’t know if you were ever going to get a chance to wipe it out again. It was nothing to hire a cab and get a cab load of beer and go out and celebrate on a beach somewhere. We could eat steak and eggs every morning, can you believe that? We didn’t have to eat those awful powdered eggs and potatoes.”

Missions that Kraft and soldiers like him performed in the Solomon Islands were vital in the war effort against Japan. The clearing of Japanese forces in the South Pacific laid the foundation for future battles such Iwo Jima and Okinawa to take place. Japan would sign its unconditional surrender on September 2, 1945.

“I can’t overstate enough how outstanding Mr. Kraft’s generation was and is,” Young said. “They met the challenges of the Depression and they met the challenges of WWII.”

Following the war, Kraft made a run at civilian life before re-enlisting in the Army. Upon retirement from the military, Kraft began working for Boeing in Seattle, Washington. After 30 years at Boeing, Kraft retired then he and his wife Mary eventually settled in the Umpqua Valley where they reside today.

By the end of the next decade or so, there will likely be no surviving veterans of WWII. Their stories will no longer be told by the voices that experienced them. Professor Young offered his thoughts towards the future.

“I am an optimist about the future,” Young said. “We are headed for the stars as democracies. Democracies will win and decency will win thanks to a generation such as this stepping in when needed.”